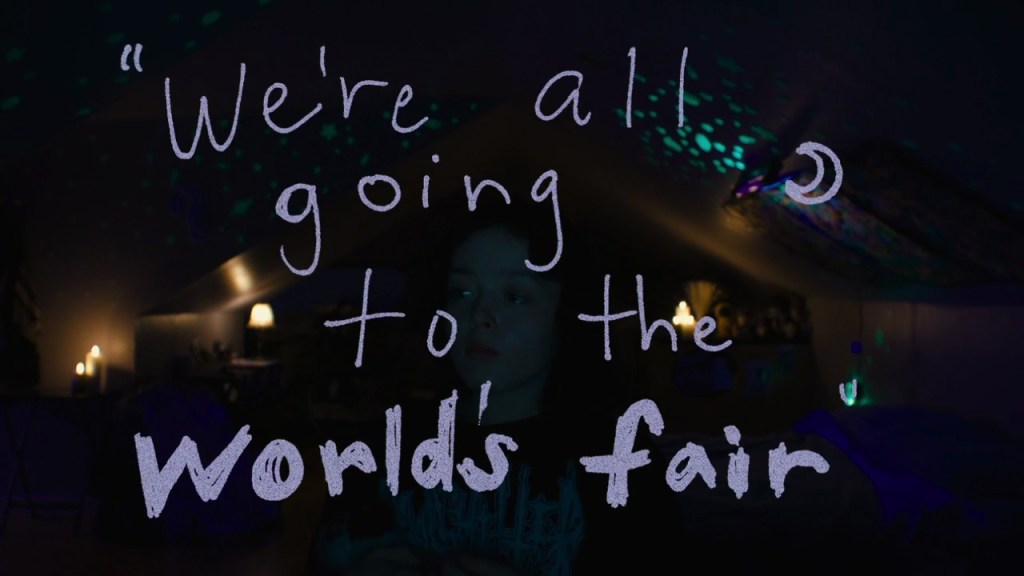

If I were to imagine We’re All Going to the World’s Fair as a physical object in the world, I think it would be a notebook. It would be a dog-eared little number, its leatherette cover flaking away. Cheap but well loved. It would be an object filled with personality on the outside. If World’s Fair gets anything right, it’s just such an aesthetic. Beyond its fixation on a particular flavour of teen angst, World’s Fair does not work very well – using an approach that is often aggressively elliptical, and fails to take chances. Surely, this gen z tone poem was not built for me, but if it worked, that wouldn’t matter at all.

Casey (Anna Cobb) is a lonely wanderer, an isolated teenager. Her social interactions are restricted to her phone, and laptop. Nary do we see another character, friend, or foe, but from the glow of Casey’s screen. Over the course of the film, Casey becomes fixated on playing a game – We’re all Going to the World’s Fair – where players evoke some class of entity, then document the changes happening to their bodies, and consciousness, via video posts. Her activities draw the attention of a fellow player – an older man by the handle JLB.

Nothing much happens in World’s Fair. The film takes an elliptical tone, and tacitly refuses to resolve anything it brings up. Such a papery adherence to the narrative falls flat insofar it is extremely difficult to care about, or understand, Casey. Casey occupies the screen about 90 percent of the time, and yet we are not aligned with her. Her immaturity, the way she chooses to spend her time watching drivel online, coupled with a lack of character development, or other characters, makes the whole thing really very dull. It’s like that notebook with the flaking leatherette cover- but when you open it the pages are blank.

Simply, World’s Fair’s interrogations of moving image media are about as paper-thin as its narrative, and not approached very creatively.

These stylistic decisions have a point – and yes I’m aware of the horror subculture it is lampooning – in respect of moving image media, the blur between fantasy and reality, and the illusion of sociality before a screen. There’s a certain something to be said about Casey falling into the online vortex as if accessing the spirit realm, but that’s another thought-tree entirely. Simply, World’s Fair’s interrogations of moving image media are about as paper-thin as its narrative, and not approached very creatively. The audience is taken in and out of computer, and phone screens, the totalizing effect being that we’re just watching videos inside a movie.

If one considers World’s Fair in its hybridity – as a narrative occurring in both the material world, and online, one may ask why it limits itself to the surface of actual screens as the totality of its representational power. Why not exploit the lo-fi narrative to really go deep on that line between fiction and reality? It’s like the filmmaker left themselves a wide-open space to experiment but forgot to show up. Long shots of Casey staring at her laptop set a tone, but it just goes on like that. Do we really need a whole movie about what it feels like to chat with strangers on your computer late at night? The film never proves itself clever enough to subvert the aesthetics of the thing it is satirizing – which seems, to me anyway, a little bit important if your aim is to critique, or comment, or whatever. World’s Fair caves to the yawning time dilation that occurs between a depressed teenager, and the tumult of her feelings, but totally subverts its strength as a tone poem by taking itself on as an academic think-piece. Between its refusal to resolve narrative expectations, and the aggressive restraint on characterization, the film comes to feel like an idea for a thing to say, rather than a fully functioning motion picture.

Between its refusal to resolve narrative expectations, and the aggressive restraint on characterization, the film comes to feel like an idea for a thing to say, rather than a fully functioning motion picture.

The ellipticity comes out as deliberate, contrived, and joyless. The world of the film is totally uninteresting. Its narrow focus on Casey is to the exclusion of anything else, and just who is Casey? Am I supposed to believe that she knows no one, and never talks to her parents? Loneliness isn’t a personality trait. Casey’s isolation, and alienation, would feel much more immediate, pressing, dare I say, important if there were some contrasts between the world, and her subjectivity. It’s as though World’s Fair wants to say something, without saying it at all, while depriving itself of the means to say it in any case because it’s too stripped down. It falters between approaches solemnly, and humourlessly.

Or maybe I just don’t get the humour. Many who approach this film come away saying that it wasn’t made for them, and that’s why they did not like it. I think that’s stupid. People in their 30’s are not so culturally distinct from a teenager like Casey that they can’t understand the movie. Maybe the movie just isn’t very good. Maybe the movie is a debut feature by a talented filmmaker still trying to find their voice, and not a rarefied cultural object. Not yet anyway. Director Jane Schoenbrun has a film coming out this year – I Saw the TV Glow – early reviews at SXSW are positive, but some highlight similar issues to World’s Fair. In any case, TV Glow has more than one character, and I’m keen to see how Schoenbrun functions in a more dynamic cinemascape. I could surely not recommend World’s Fair but to the most fanatical lo-fi aficionados, lovers of tone poems, and those who need an entire movie about what it feels like to chat with strangers at night online. Surely, none of us film lovers got enough of that when we were Casey’s age. Time to relive it.