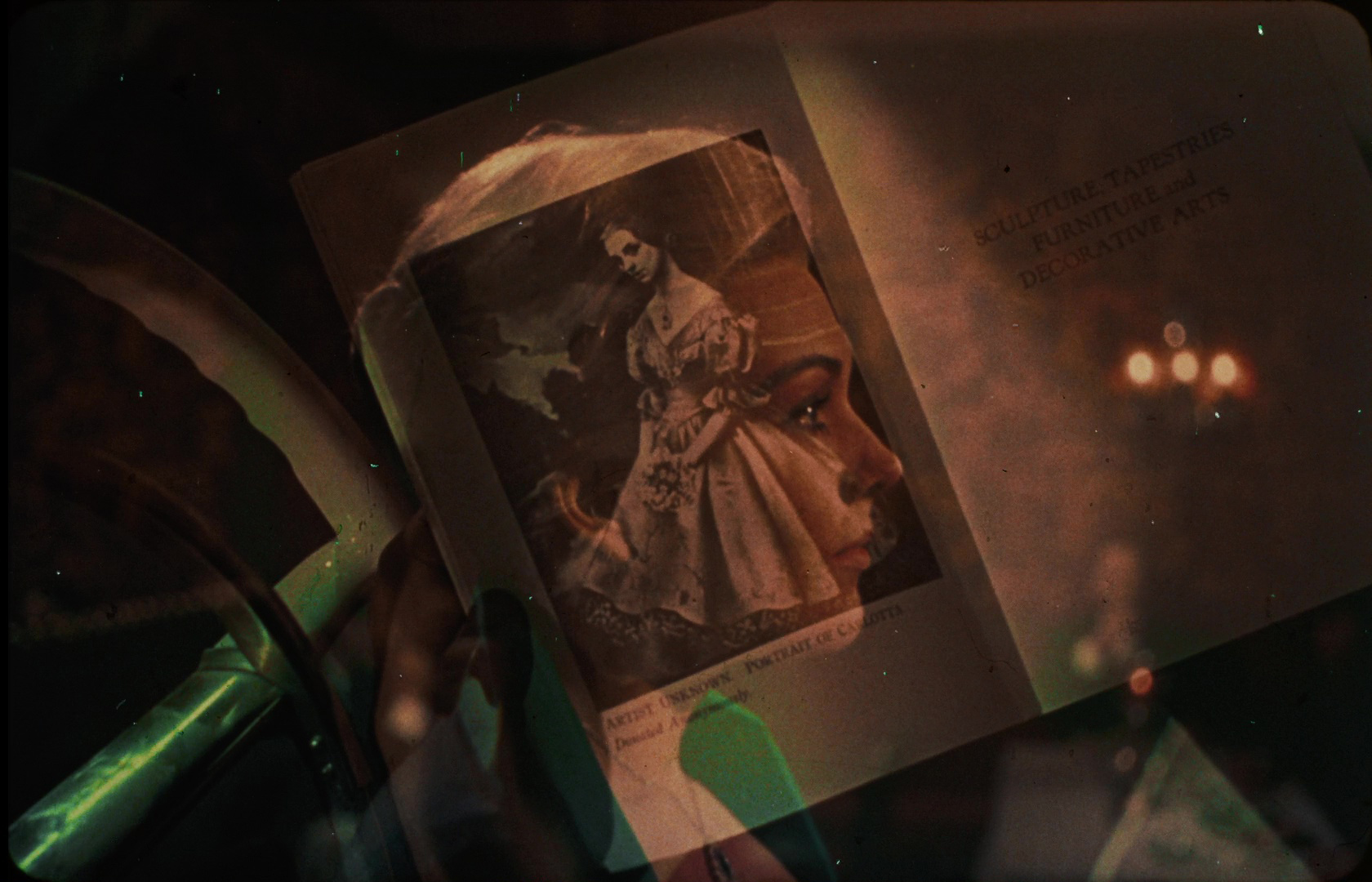

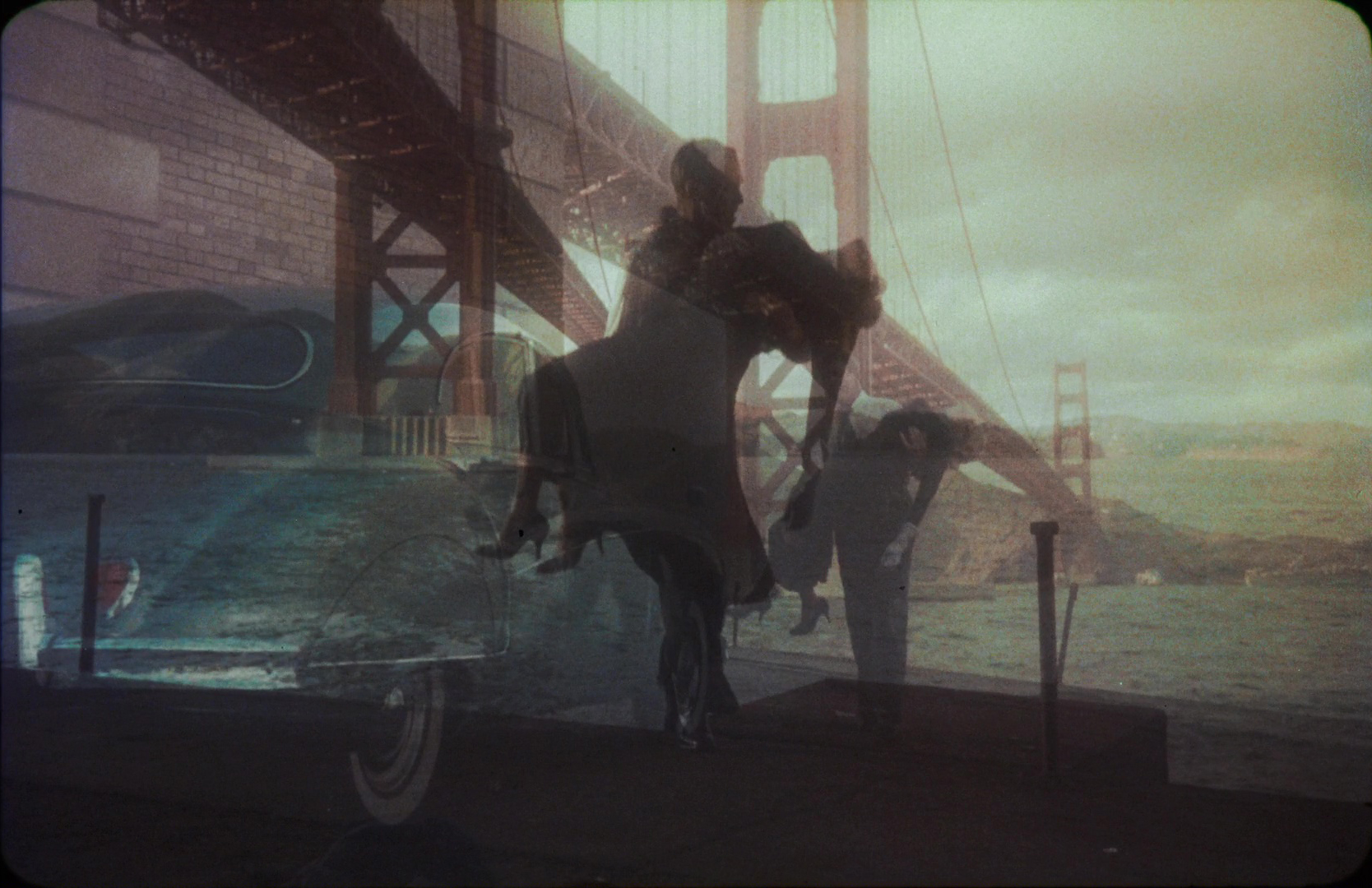

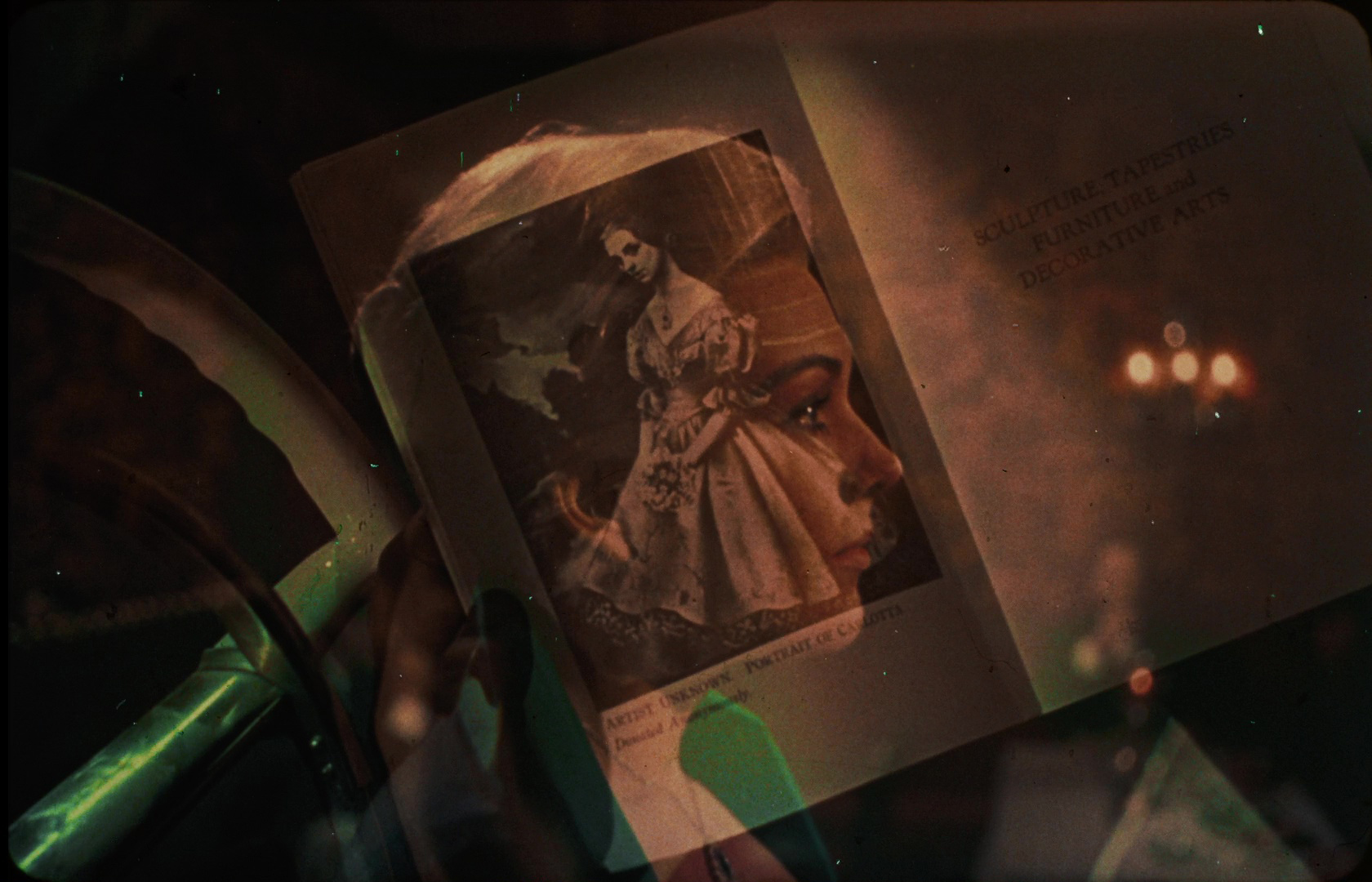

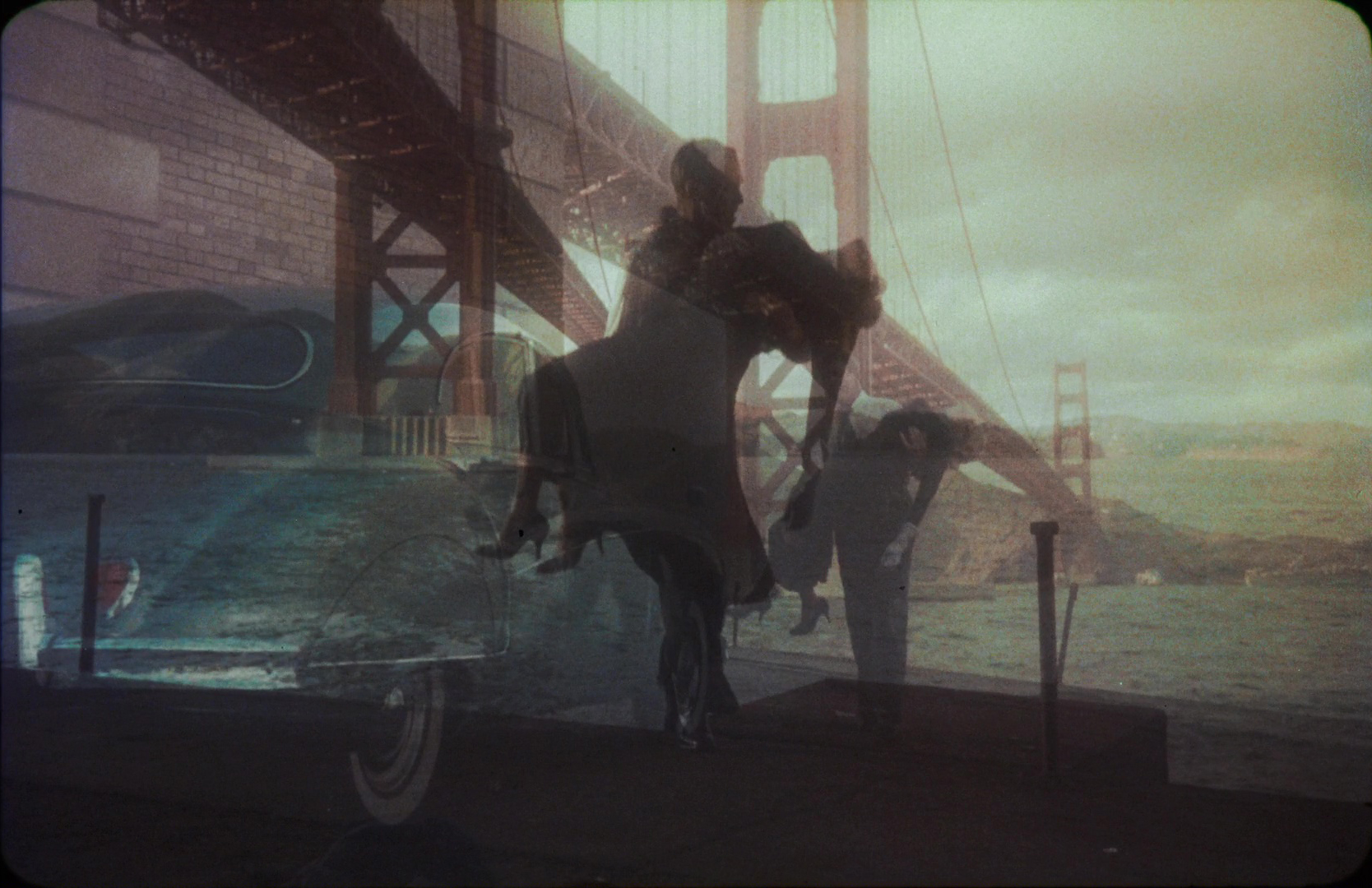

A collage of dissolves from an unofficial scan of Hitchcock’s 1958 masterpiece.

There is nothing worse then an unserious film taking itself too seriously. Civil War has all the quality of a mid-tier episode of The Walking Dead.

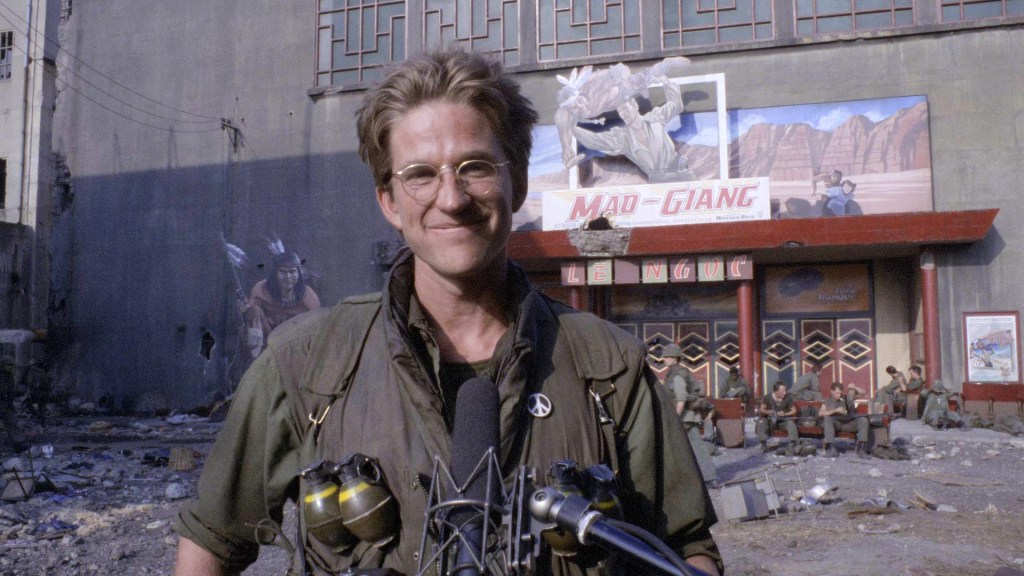

It has been a long time since the likes of Stanley Kubrick, Robert Altman, and Hal Ashby, et al, were on hand to make searing artworks on the hypocrisies of the day. American political cinema of the 1970’s and 80’s was a beast. Take Private Joker (Matthew Modine) in Full Metal Jacket when he stares down the camera to tell us about all the “exotic” people of an ancient culture he has come to kill. The irony of his words cut like a knife through post-Vietnam America. Then there is the slow-zoom out in the final scene of All the Presidents Men. It presents a titillating tableau: Nixon’s inaugural ceremony blares on the television while Woodward and Bernstein bang out his downfall on their typewriters. Sidney Lumet’s Network lampooned greedy TV execs, so desperate for a bloody scoop that they onboard a murderous domestic terrorist group. These films are powerful because they make powerful statements about politicians, war, American myth, journalism, and the discursive power of screen media. Moreover, they’re not afraid to make those statements. They exist on a continuum of thoughtful cinema that bypasses partisan nonsense and cuts to the very core of our human concerns in the 20th century: the difference between war and murder; truth and lies; news and a paid fabrication.

I say all this to juxtapose these earlier masterpieces of political cinema to the lukewarm offerings of the 21st century: Alex Garland’s Civil War. Civil War is so toothless, sloppy and risk adverse that it says nothing at all. And I don’t think it’s because the film doesn’t want to make a statement, I think the film is too stupid to come up with one. It’s capitalistic excess at its very worst: a film trying to take advantage of a very specific cultural moment while offering no salient commentary or satire. It’s less a political cinema than a reactionary one.

Not only does Civil War embody no memory of its political forebears, it presents itself as a road movie with barely a concept of a road movie. A group of photojournalists must drive to Washington D.C. in time to document the “Western Alliance” capture of the U.S. president. Each situation they encounter on the road is more anonymous than the last: a gas station full of rednecks holding faceless hostages; commando Jesse Plemons waving a gun over a mass grave of more faceless people; a booby-trapped Santa’s Village.

Garland misses a vital and obvious opportunity by merely placing this film on the road with no impression of American road films. Get Wim Wenders on the horn. Think of Paris, Texas, where the road imagery links the viewer to Travis’ (Harry Dean Stanton) fractured family and identity. Think of Thelma and Louise where the characters encounter people and situations that directly reference their actions and the themes of the movie. This is basic stuff. The characters in Civil War mostly encounter random things that have anything to do with them. No one is making choices. The bones of the story have osteopenia: the characters are just driving to D.C. and running into stuff. Is there some grandiose symbolism regarding political polarization, new screen media, the United States, and Santa’s Village that I am missing here? Doubt it.

The characters are not much better. Lee (Kirsten Dunst), saddled with a perpetual look of determination, plods through the film, dispensing oh-so-adroit wisdom to the ingénue la photographie Jessie (Cailee Spaeny). The other leads make even less of an impression, and the characters who die are just red shirt inserts designed to take bullets. Such missteps lower the stakes in a film where everything should be at stake. Civil War also cannot handle a bit of logic surrounding its most important story objects. Why is Jessie shooting and hand developing 35mm film in a war zone when she doesn’t have to? Why is she shooting with that camera at night? Surely, both of these are suboptimal uses of her time as a photo-journalist. Half her pictures would be blurry and under exposed. The object negates its own meaning if you can’t imagine why it’s there in the first place.

And it just goes on like that. It might take a leap of logic to imagine what sort of militia force would let journalists take photos of them murdering unarmed people. You may then ask yourself why such blood thirsty cretins wouldn’t just murder the journalists too. Couple these preposterous scenarios with very bland filmmaking and you might have the most forgettable political thriller ever made. It looks like an advertisement. So many shots are in shallow focus and also in the dark. If that’s what you’re doing, why not just shoot the whole movie on an iPhone? It’s cheaper.

What is the consequence? How are the actions of the characters driven by an engagement with media? The entire point of critiquing journalism in a film such as this is because it is a matter of tremendous consequence. But here, visually and narratively, the audience has nothing to grab on to. Garland did not have to take a partisan stance in order to give his film thematic heft. Not being American, he was in a unique position to do so. Instead, he coyly denies engagement even of the allegorical variety. The “Western Alliance” – a partnership between California and Texas – lets us know that, not only is this film unserious, it’s also unaware of opportunities for black comedy since it seems totally unaware how funny that is. There is nothing worse than an unserious film taking itself too seriously. Civil War has all the quality of a mid-tier episode of The Walking Dead.

Why do we accept these mediocre thunk pieces? Is there nothing better on TV? There is something deeply cynical and unethical about taking something as serious as a nation’s ideological divide and turning it to pablum. The central question of the film is “What kind of American are you?” the implication being that regardless of the answer to that question, everyone asked it is indeed an American. That’s about the only thing that matters: getting Americans to buy movie tickets. Civil War is at best a lazy capitalization on a cultural moment, and at worst totally stupid.

An image collection of cinema’s leading ladies in profile.

An image collection of cinema's leading ladies in profile shots.

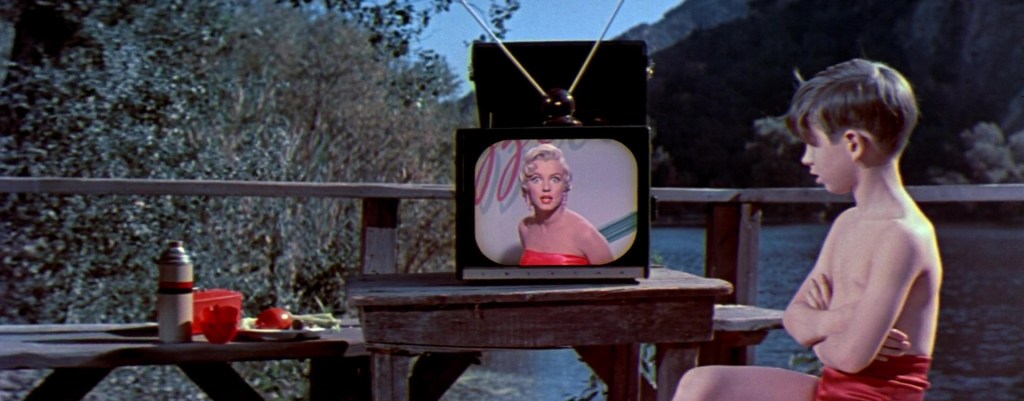

An image diary of shots in films featuring a television, or something like it.

The aesthetics of silence play a crucial role in our understanding of evil in the brilliant, but flawed, The Zone of Interest.

Lexie’s Cine Obscura is also a Youtube Channel!

This essay is the text of a video essay of the same name, which can be viewed here: https://youtu.be/9BXXAaDgvNo?si=krlaeF47l6YmYNr3

Some films bother me for months. Not because of anything represented or said, but because I feel as if there is some key point about it I have not fully understood. I usually express that as not knowing what a film is “about” – much to the amusement of those around me. I think what I mean is that I’m not sure what mechanism the film in question has provoked ambivalence in me. The Zone of Interest is my latest entry. I walked out of the theatre feeling… unclean. I chalked it up to the way the film conveyed its message by way of flippancy – like Hedwig (Sandra Hüller) putting on lipstick stolen from the incoming prisoners of Auschwitz. The film embodies a refusal to see in every sense. Even the photographs of Hitler do not look out toward the room. A film that formulates itself around the aesthetics of visual silence is a tremendous experiment indeed, and no artist should be faulted if the experiment fails, as I think it does in The Zone of Interest. If the purpose of this film is to convey the aesthetics of evil, bound up by an aesthetics of silence writ in a refusal to see in the cinematic sense, and link that to the psychology of man, the film has failed because it itself refuses to see what makes up men.

The Zone of Interest cultivates its aura of uneasy disgust by keeping the camera away from the characters. There are very few eyeline matches, or close-ups. Characters sleep in twin beds. The doubling motif is common but somewhat subtle. The static cameras in the house convey little logical space. The camera flips itself during key moments to mirror the scene and reflect the dual action at play. Quiet moments of expression like this dot the film and occur most acutely during a rare tracking shot across the garden with Hedwig and her mother. Characters don’t really see themselves in mirrors – a pointed stylistic turn that keeps them out of the realms of vision.

Such is to say: they cannot see beyond themselves to the horrifying events occurring just beyond the garden wall. Only the camera really knows what is happening. Which is sort of the problem. Everything has been outsourced to a camera-eye that assumes a specious gaze as one of history. One of the few eyeline matches occurs at the very end of the film – when Höss is walking down dark staircases during a Nazi gala and dry heaving every few steps. He stops and looks up at the camera – at us – and the scene cuts to a door revealing real footage of staff maintaining the Auschwitz Museum.

Such a historical gaze is assuming that the Höss family had some measure of capability to recognize what was happening and refused to do so. But that assessment totally misunderstands the nature of evil, and what we mean by the “banality of evil”. Because the banality of evil is not a refusal to see, it is a refusal to know there is anything to see because the psyche has been so captured. Evil becomes a way of life, and a reason to live. In 1945, with the allies closing in and defeat assured, the dregs of Nazi high command ordered the German people to fight to the last child – such was their dedication to the horror they wrought upon the world. Evil then becomes a question of the epistemological origin of emotion and action. The Zone of Interest is less concerned with the implications of that reality, and more concerned with a cinematographic exercise that seeks to comprehend evil as something without humanity behind it – turning the camera into an objectif that bears itself up as a documentarian of concept – but such is an unattainable vision – a mismatch between story and form.

There is a total unreality to this film that is not native to its subject matter. The hyper excited formalism – there to embody the implicit evil of humanity – is much tamer than if the film had complicated our spectatorship by asking us to empathize with them. Some of it feels too much like a joke sometimes – like when one of the Höss sons is playing with human teeth in his room. It’s so winky – as if to say, “yes you are watching a film about the Commandant of Auschwitz”. It relies too much on recognizing the knowledge we have, and referencing things we know occurred, and can contextualize – like the ash from the camp furnaces being used to fertilize the Höss’ garden. The film treats its images as things that can reference a reality beyond themselves. As such they can only be understood on those terms. The image of the ash fertilizer means nothing if the viewer does not know the history behind it. In fact, it’s difficult for me to say how much sense the film would make to a person with no knowledge of WWII or the Holocaust. So, the film itself becomes an obscure object perpetuating the very refusal to see it portrays. It wants to say: “evil people are not ‘somewhere else’, they are right here. They live in houses, and they eat off plates.”

Yet the aesthetic make-up of Zone does not speak to that beyond the superficial.

Zone fails to bear up in respect of its subject matter because it does not comprehend the characters as real people – only avatars of history. In order to understand evil, we must understand people. Downfall, Oliver Hirschbiegel’s German-language Hitler (Bruno Ganz) in the bunker film – was powerful, and controversial, because it treated its subject like a real person. It complicated our spectatorship not by winking, or showing us gratuitous atrocities, but by looking at the nature of human psychology. All men are capable of great evil and that is the thing we need to comprehend, but Zone’s camera pre-emptively negates that possibility. The characters cannot even see each other.

It is notoriously difficult to make a film about the Holocaust. How can cinema possibly comprehend the totality of man’s unstoppable, mechanistic, cruelty to man? I’m not so sure it can. I commend Glazer for trying. The filmmaking in Zone is virtuosic, and it will stand up on that alone. But as an entry into the canon of Holocaust cinema it leaves much to be desired.